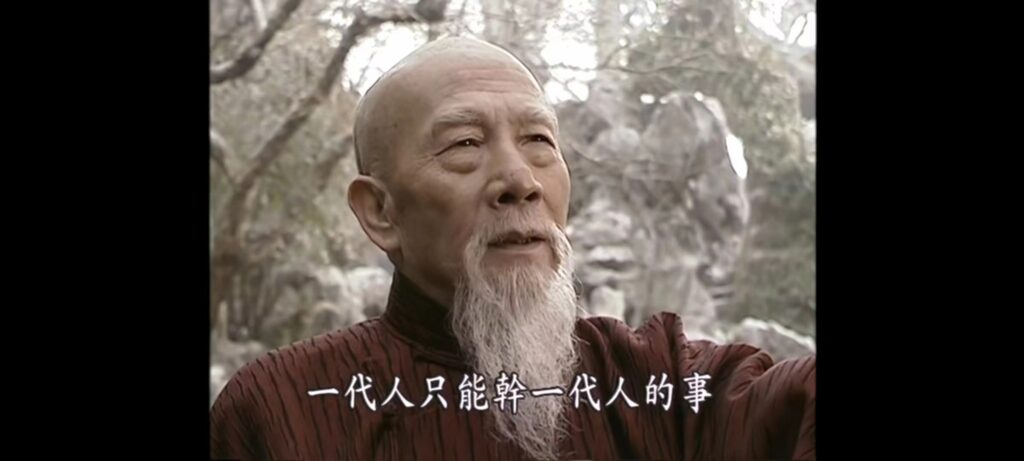

“卓如啊,一代人只能干一代人的事”,李合肥对年轻的梁任公感叹道。意思应该是,我做我的“裱糊匠”,你们后生一代干好自己的事儿。

对话是电视连续剧《走向共和》里的一个场景。李鸿章督粤时,梁启超前往拜会。梁向李中堂提出上中下三策,试探并暗劝李大人当行上策,拥两广自立并成为大伯理玺天德(President)。李选了下策,受命回京,收拾两宫西狩后留下的破烂残局。电视剧中的会面和对话应该是虚构的。但所谓上中下三策,梁任公所著《李鸿章传》中则明确提到了:

“当是时,为李鸿章计者曰:拥两广自立,为亚细亚洲开一新政体,上也;督兵北上,勤王剿拳,以谢万国,中也;受命入京,投身虎口,行将为顽固党所甘心,下也。”

电视剧中,梁启超自己扮演了“为李鸿章计者”。

《李鸿章传》对李中堂的分析和评价深刻且精辟。李是“纯臣”和“庸臣”,其为“权臣”都勉强。李的认知基础是孔教,孔教“义理既入于人心,自能消其枭雄跋扈之气,束缚于名教以就围范”。《传》中谈及一轶事,亦可管中窥豹:

“李鸿章生平最遗恨者一事,曰未尝掌文衡。戊戌会试时在京师,谓必得之,卒不获。虽朝殿阅卷大臣,亦未尝一次派及,李颇怏怏云。以盖代勋名,而恋恋于此物,可见科举之毒入人深矣。”

认知是行动之基础,行动往往超越不了自身认知所设立的藩篱。李中堂当有自知之明,“自立”的破格之举,他内心无法接收,遑论为之。

一代人有一代人的认知和行为模式,上一代视为不可思议的事情,下一代会认为是理所应当。一切留给时间,急也没用。但不能放弃努力,“诸君莫作等闲看”。历史三峡中,此一代奋楫破浪划不出去,下一代或下N代当持续努力扬帆挥桨。

“Each generation can only accomplish the tasks of its time.”

“Zhuoru, each generation can only accomplish the tasks of its time,” said Li Hefei(a.k.a. Li Hongzhang) to the young Liang Rengong(a.k.a Zhuoru or Liang Qichao), implying that he would do his work as a “paste-up worker,” while the younger generation should handle their own tasks well.

This dialogue is from a scene in the TV series “Towards the Republic.” When Li Hongzhang was governing Guangdong, Liang Qichao went to visit him. Liang presented Li with three strategies, subtly advising him to adopt the top strategy, which was to establish independence in the two provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi and become President. Li chose the third strategy, accepting the order to return to the capital and clean up the mess left after the Empress Dowager’s westward escape. The meeting and dialogue in the TV series are likely fictional. However, the three strategies mentioned by Liang Rengong in the “Biography of Li Hongzhang” are clearly outlined:

“At that time, those advising Li Hongzhang said: To establish independence in the two provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi and introduce a new political system to Asia is the top strategy; to lead troops northward to support the emperor and suppress the Boxers, thus apologizing to the nations, is the middle strategy; to accept the order to enter the capital, risking his life, and inevitably becoming a target for the conservative party, is the bottom strategy.”

In the TV series, Liang Qichao himself played the role of the adviser to Li Hongzhang.

The “Biography of Li Hongzhang” provides a profound and incisive analysis and evaluation of Li. Li is described as a “pure minister” and a “mediocre minister,” barely even a “powerful minister.” Li’s foundation of cognition was Confucianism, which “when deeply ingrained in the human heart, naturally eliminates the domineering and arrogant spirit, binding it within the norms of Confucianism.” The biography also mentions an anecdote, providing a glimpse into his character:

“The greatest regret of Li Hongzhang’s life was that he never held a literary office. During the 1898 Imperial Examination in Beijing, he was certain he would achieve it, but he did not. Even though he was one of the ministers reviewing the exam papers, he was never assigned the role, which made him quite resentful. Despite his outstanding contributions, he remained deeply attached to this. This shows how deeply the poison of the imperial examination system had penetrated.”

Cognition is the foundation of action, and actions often cannot transcend the boundaries set by one’s cognition. Li Hongzhang likely had self-awareness; he could not accept the unconventional act of “establishing independence” in his heart, let alone act upon it.

Each generation has its own modes of cognition and behavior. What seems inconceivable to one generation may seem perfectly normal to the next. Everything must be left to time; rushing is futile. But one should not give up the effort. “Do not take this lightly, everyone.” In the historical rapids, if one generation cannot navigate through, the next or subsequent generations should continue striving, raising their sails and rowing forward.

劳劳车马未离鞍,

临事方知一死难。

三百年来伤国步,

八千里外吊民残。

秋风宝剑孤臣泪,

落日旌旗大将坛。

海外尘氛犹未息,

诸君莫作等闲看。